Many years ago, when I was engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the ferocious winters of Montreal, I was introduced (virtually) to a speaker who shared these thought-provoking words “What makes you angry? It is a clue to something you were purposed to address.” The words have echoed in my mind since then, especially when I see something upsetting. And that happened this week.

I was watching a run of the mill news story featuring German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, holding a town hall meeting in which a young immigrant girl, living in Germany, expressed her desire to continue her studies in Germany. The problem? She was a refugee from Lebanon, now facing deportation. As she spoke of how painful it was to watch her friends go on to study when she could not, she cried. Merkel’s response:

“When you stand in front of me and you are a very nice person, but you know . . . there are thousands and thousands [of people] and if we say you can all come and you can all come from Africa… We can’t manage that.”

Immigration is a loaded topic and there are reasonable arguments both for being lenient and selective in policy. What got to me is that the simple desire of this girl to study where she lived was being held hostage to a policy and to the limitations of her home country. It reminded me of my experience at a Kenyan hospital earlier this year when a mother presented her child with a spinal birth defect at 9 months instead of the recommended 48 hours which caused lower limb paralysis and incontinence. Why not earlier? Cost. The mother could not afford it. It is frustrating when people do not have access to basic education and health. But what is more upsetting is when we settle for sensible answers and say things like “There are not enough resources to go around.” or “We can’t take everybody.” Where is the creativity? Where is the resolve that says this is unacceptable and sensible answers are not enough?

It was not sensible to suggest fighting malaria with a fence that shoots out lasers to kill mosquitoes . . . a “Phototonic Fence” is almost ready for market.

It was not sensible to have a patient play guitar during brain surgery, but that’s how a neurosurgeon recently conducted an operation to ensure the patient’s brain function was not being compromised.

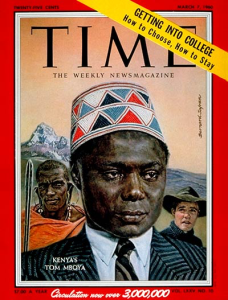

It was not sensible to suggest that the nation with the highest percentage of its population engaged in mobile banking would emerge from sub-saharan Africa . . . today, that nation is Kenya.

It was not sensible to suggest that internet service can be provided to a rural community without electricity. The creative thinkers at Mawingu Networks are doing just that using solar energy and “television white space,” unused television frequencies.

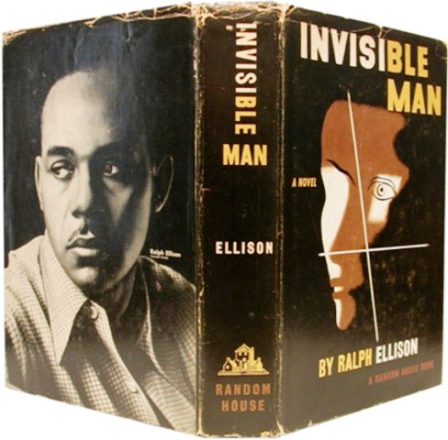

No one is saying these problems are easy, but we won’t solve them by conventional thinking. This could be reduced to another “thinking outside the box” message but this imperative goes deeper. I think we all harbor real doubts about whether some problems can ever be solved, but if we see something isn’t right, it should drive us to do something about it regardless. The creative knowledge is there and our access to each others’ thoughts is unprecedented.

You’d be amazed what you can find.

Consider a silly experiment that I carried out this week. First, let me say that I am always astounded when I look up something on Google at how many people have asked the question before, even when it’s quite obscure. So I decided to make up a highly ridiculous search request, just to see if the question had been asked.

I typed in the question “Do onions make good pillows?” I did not find a hit with that exact question, but someone did ask whether he should sleep with an onion in his armpit. Why??? Apparently, in some regions of South Asia, it’s a trick to cause a fever for kids to get out of school. I have no idea if this works and have no (immediate) plans to test it. But if it is true, how was that discovered?? Minds are churning every day and we have access to these minds.

It bothers me when we settle and use words like “reasonable”, “realistic” and yes, “sensible”. This is not arguing for rebellion for rebellion’s sake, or self-indulgent attention seeking. And, of course, there is a place for planning and counting the cost. But, there are real heart wrenching issues we face today that are costing lives and hope that can only be confronted successfully if we’ll take the risk. Spectacular success begins with the willingness to fail, spectacularly.

Let’s stop being sensible.